Japan is one of the most expensive countries in the world for would-be political candidates – a fact which has often been a topic of debate and criticism. The baseline cost of putting yourself forward as a candidate in a major election is a deposit of ¥3 million (roughly US$28,000), dramatically higher than comparable deposits in countries like the United Kingdom (£500, roughly US$620), Australia (A$2000, roughly US$1400) and more than twice as expensive as in South Korea (KR₩15,000,000, roughly $12,500). Past criticisms of the deposit system focused on the fact that by making it as expensive as an ordinary person’s annual salary, it prevented working-class people without major party support from participating in politics – but anyone who has been following the Tokyo gubernatorial election campaign over the past two weeks would be forgiven for wondering if perhaps the real problem with the deposit is that it isn’t enough of a barrier.

The 2020 election campaign for the governorship of one of the world’s largest cities has devolved into a circus – one with very few acrobats but plenty of clowns. The ¥3 million deposit (which is only refunded to candidates who win at least 10 per cent of valid votes cast in the election) is supposedly designed to ensure that only serious candidates stand for election, setting the bar high enough to exclude cranks, comedians, and self-promoting celebrity wannabes. In this, it has failed utterly. While the almost inevitable victory of incumbent governor Koike Yuriko meant this election was never going to be particularly edifying, the clowning of a large number of candidates using the election to boost their YouTube subscriber numbers and celebrity status has turned it into outright farce, sucking all oxygen out of what should, at least, have been a chance for Koike’s record in office to be debated in public.

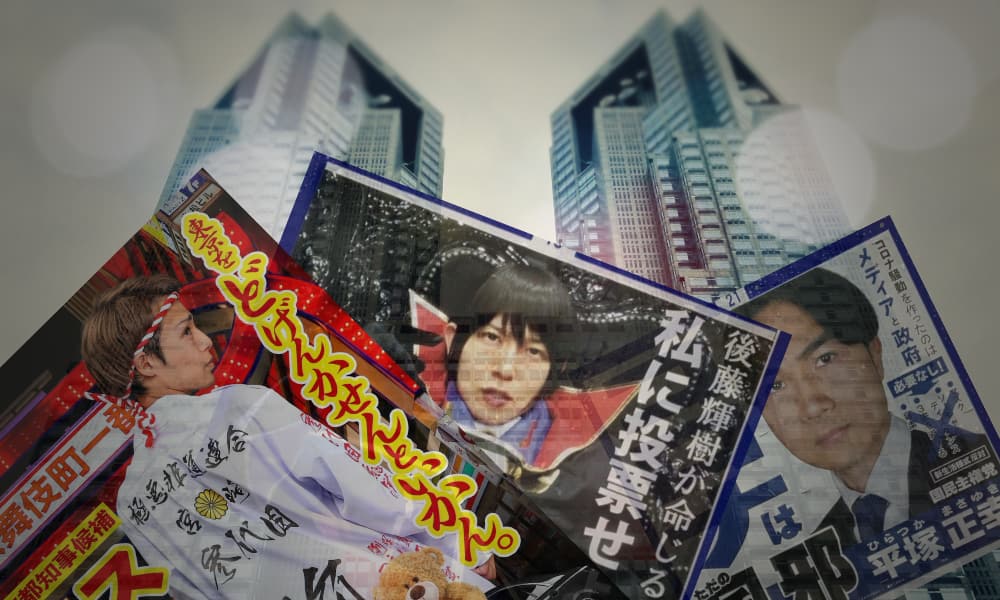

Over the past weeks, every household in Tokyo received a newspaper-style publication giving each of the 21 candidates a space in which to set out their stall; each of them also received a legally mandated broadcast slot on NHK television. Among the candidates being given serious airtime in electoral publications and broadcasts in this manner are a conspiracy-theory spouting YouTuber whose election slogan is “Coronavirus is just a cold;” another man who claims in his electoral literature to have discovered a cure for coronavirus; a social media “influencer” and musician whose intention to use the election as a platform for self-promotion extends to including QR codes for his social media accounts on all his election literature; and perennial election “comedian” Gotō Teruki, who during his NHK electoral broadcast stripped off his clothes to reveal a brown-stained adult nappy underneath.

Candidates given official airtime include conspiracy theorists, social media influencers, and a man in a brown-stained nappy.

This is to say nothing of Tachibana Takashi of the “Protect the People from NHK Party,” who is running in this election as a candidate for the “Horiemon New Party” – named for disgraced former entrepreneur and latterly celebrity YouTuber Horie Takafumi, whose face appears on its posters but (like his expression on said posters) is ambivalent at best about his actual involvement in the party. The Horiemon New Party is actually running three candidates in the election – which is ridiculous in an election with only one position on offer, of course, but only Tachibana’s name appears on the posters and other literature, meaning that the extra ¥6 million it cost to run the other two candidates was spent purely to allow Tachibana to have three times as much space as every other candidate on the poster boards spread throughout the city.

This strategy points at the actual problem laid bare by this year’s election. ¥3 million is a very, very large amount of money for a person who legitimately wants to try to make a difference through the democratic political system – and 10 percent of the vote an enormously high bar to clear in order to get it back. There are a few of those people standing as well, single-issue candidates using the election to draw attention to political campaigns around animal rights or the reform of laws related to prescription drugs, and for them the choice to stand in the election reflects a choice to spend what is undoubtedly a very significant amount of their campaigning budget in the hope of drawing attention to the issue. ¥3 million is, however, absolute peanuts for someone who is viewing the whole thing as a media platform. For less than $30,000, each candidate gets several minutes to broadcast whatever they want on NHK, an official statement delivered to every single household in Tokyo, and a prime outdoor location on every street in the city for their posters for two weeks. For someone investing in building their own celebrity, there is simply no other marketing offering out there which offers that kind of value – let alone the added bonus of guaranteed media coverage for whatever wacky antics you get up to along the way.

It can feel a bit churlish and grumpy to be complaining about joke candidates in elections – in many countries they’re a historic part of the electoral process, an affirmation of freedom of speech and, in their own way, a powerful reminder of democratic values. Lord Buckethead standing against UK Prime Minister Theresa May in 2017 is a great recent example of how a satirical or comedy candidacy can help turn an election into a great leveller, forcing the leader of a major G7 nation to share a stage with a bargain-basement knock-off of Darth Vader to wait and hear which of them is returning to a seat in Parliament. Japan has its own tradition along the same lines, and indeed, one of this election’s more ludicrous figures, Gotō Teruki, was responsible for a classic of the genre with his almost-but-not-quite rule-breaking nude poster for his campaign for the Chiyoda Ward Assembly in 2015. There is something inherently egalitarian and humbling about citizens being able to poke fun of serious politicians in this way – and even to register their displeasure with the system by voting for the overtly ridiculous.

Koike’s victory is all but certain – but the preponderance of self-promoting candidates has drowned out much-needed discussion of her actual record in office.

What’s different about Tokyo’s 2020 election is that the cavalcade of ridiculous candidates are not, for the most part, earnest single-issue campaigners or devoted satirists with high-minded ideas about democracy. They’re hard-nosed self-promoters who have recognised the business opportunity which the election presents and have no qualms in clambering over their city’s democratic processes for a bit of a boost to their YouTube subscriber numbers. One could argue that their presence doesn’t actually make much of a difference – Koike remains enormously popular and has received a significant boost from her public handling of COVID-19, while her only serious challenger, Utsunomiya Kenji, is a perennial also-ran in Tokyo elections (finishing second to Inose Naoki in 2012 and then to Masuzoe Yoichi in 2014, though in the latter case he managed to beat former Prime Minister Hosokawa Morihiro despite heavy support for Hosokawa’s campaign from another former PM, Koizumi Jun’ichiro). Yet this is a serious election for a role with very significant power over the lives of everyone who lives or works in Tokyo, and the fact that Koike’s victory is a foregone conclusion shouldn’t have insulated her from discussion of her record in office – which is pretty flimsy at best, having achieved very little of an already distinctly unambitious manifesto despite controlling not just the governor’s office but also the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly through her neophyte-heavy local political party, Tomin First.

All discussion of Koike’s record in office or her policy manifesto – let alone of the alternatives offered by her serious challengers – has been subsumed in the noise created by the coronavirus conspiracy candidates, Gotō Teruki’s soiled nappy, or the repurposing of two “Abenomask” face masks as a makeshift bra for the poster photograph of a woman running for Tachibana’s party in an Assembly by-election in Kita Ward. Utsunomiya’s policy platform is quite different to Koike’s, and even if his chances of winning were always minimal, the campaign should at least have offered an opportunity for his ideas and those of other fairly serious candidates like Reiwa Shinsengumi’s Yamamoto Taro or Ishin no Kai’s Ono Taisuke to be discussed, weighed, and considered by the public. Instead, we’ve been treated to a three-ring circus of the absurd, the end result of which is almost certainly going to be an incredibly low turnout election on Sunday, returning Koike to office with a half-hearted mandate and minimal actual consideration of her record, her promises, or her intentions. The serious opposition candidates themselves are not blameless – the failure of a candidate like Utsunomiya to rise above the noise also lies heavily with him as a politician and reflects a general inability to engage and excite voters – but in the face of a cohort of candidates whose objective is to use a political platform to get more Instagram followers rather than achieve any democratic goal, it’s hard to see how any opposition strategy could have been truly effective at cutting through the nonsense.

Unfortunately, there aren’t really any easy solutions to this problem – and with the floodgates now open, it’s almost inevitable that high-profile elections around the country will attract many similar opportunists in future. Simply raising the price of entry is a non-starter; ¥3 million is already high enough to keep out many people with legitimate political aims, and if Tachibana Takashi can spend three times that much on getting himself a bit more poster space, it’s clear that the point where it’s too rich for the blood of celebrity wannabes and self-promoters is going to be unworkably expensive. Almost any other bar to entry, such as qualifications, tests, or other screenings, would be grotesquely undemocratic. Short of a root and branch overhaul of Japan’s most fundamental electoral laws, it’s hard to see how “influencers” can be prevented from using the country’s elections as a cheap public profile boost. Public faith in politics is already languishing at a low level in Japan; turning major elections into circuses will only deepen the problem.

Rob Fahey is an Assistant Professor at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study (WIAS) in Tokyo, and an Adjunct Professor at Aoyama Gakuin University's School of International Politics, Economics, and Communication. He was formerly a Visiting Professor at the University of Milan's School of Social and Political Sciences, and a Research Associate at the Waseda Institute for Political Economy (WINPEC). His research focuses on populism and polarisation, the impact of conspiracy theory beliefs on political behaviour, domestic Japanese politics, and the use of text mining and network analysis techniques for political and social analysis. He received his Masters and Ph.D from Waseda University, and his undergraduate degree from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.