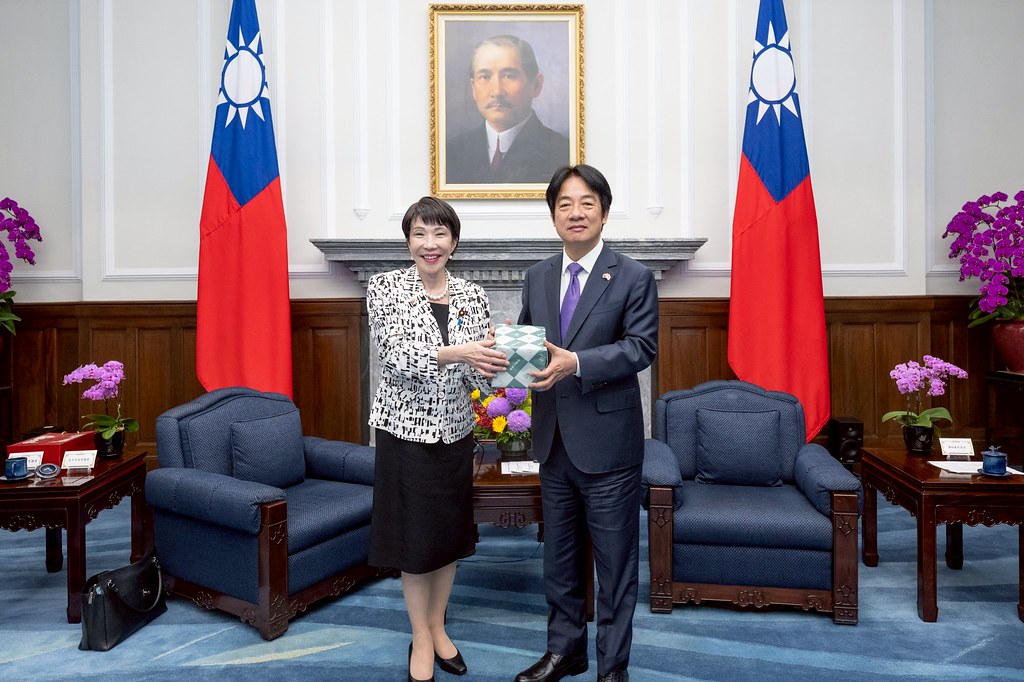

Taiwan is back at the center of Sino-Japanese relations after Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae told the Diet last week that a Chinese attack on Taiwan could pose a “survival-threatening situation” for Japan. Her comments were striking not for their content, which did not deviate from Japanese officials’ talking points over the past decade, but because Takaichi delivered them in the Diet in her official capacity as prime minister.

The severe backlash from Beijing, culminating in the Chinese consul general in Osaka graphically threatening to cut off Takaichi’s “filthy head,” has dominated the news cycle in the early weeks of her premiership. The diplomatic spat is largely framed around Beijing’s deep distrust of Takaichi and the possibility that ongoing tensions could derail the already delicate bilateral relationship. While the post was later deleted, no Chinese official has apologized for the remarks or shown signs of turning down the temperature. Days later, the Chinese Foreign Ministry took to X and urged Japan to “stop playing with fire on the Taiwan question.”

How this episode will shape the long-term course of Sino-Japanese relations remains uncertain, but Takaichi’s remarks are likely to further fuel a largely overlooked dynamic across the Taiwan Strait: the Taiwanese public’s enduring confidence that Japan will come to its rescue in the event of a Chinese invasion of the island.

Taiwanese confidence in the United States coming to its aid has wavered in recent years, most notably registering a severe dip following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet a surprisingly high proportion of the Taiwanese public believes Japan will “send its Self-Defense Forces” to defend Taiwan. In 2022, the Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation, a private think tank, found that 43.1 percent of Taiwanese respondents believed that Japan would send troops in the event of a Chinese invasion, more than the 34.5 percent who believed the United States would do the same.

A scenario where Japan sends troops to defend Taiwan while the United States sits out the conflict is almost unthinkable. Even after former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō ushered through legislation in 2015 to broaden the Self Defense Force’s ability to use force, Japan still remains one of the most constrained countries in the world in terms of constitutional limits on the use of military force, particularly when Japan itself is not under attack. The United States, while adhering to a longstanding policy of strategic ambiguity toward whether it will involve itself in a Taiwan Strait conflict, has sold billions of dollars worth of arms to Taiwan. Perhaps even more striking, these poll results—showing greater Taiwanese confidence in Japan’s military support than in America’s—came in the same year President Joe Biden declared four separate times that the U.S. military would defend Taiwan, only for his aides to walk back his remarks each time.

Chen Fang-yu, an associate professor of political science at Soochow University in Taiwan, told me that the public likely was influenced by Abe’s comments in December 2021, when he declared that “A Taiwan emergency is a Japanese emergency, and therefore an emergency for the Japan-U.S. alliance.” In the years since Abe’s comments, which he made after stepping down as prime minister, virtually every discussion of Japan’s Taiwan policy in the Taiwanese media has invoked that phrase.

While Abe’s stature as the longest-serving prime minister and his unparalleled influence within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party lent his words the most weight, he was far from alone among Japanese political elites in providing rhetorical support to Taiwan. Months before Abe’s comments made global headlines, then-Deputy Minister of Defense Nakayama Yasuhide said at a U.S. think tank event that “we have to protect Taiwan as a democratic country.” The Taiwanese public’s tremendously high level of admiration for Japan—a rarity among Japan’s former imperial colonies—helps sustain this confidence that Japan would defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion. Yet as RAND Corporation expert Jeffrey Hornung noted following Abe’s 2021 remarks, “Japan is not committed, nor has it ever pledged, to defend Taiwan.”

And even if Japan supports Taiwan’s defense by providing logistical assistance to U.S. forces or allowing the U.S. military to use bases in Japan to counter Chinese operations, Tokyo’s actions will most likely hinge on Washington’s decision to intervene first.

This distinction—the extent to which Japanese intervention in a cross-Strait kinetic conflict is linked to U.S. intervention—may be less apparent to the Taiwanese public, where the question of U.S. reliability is hotly contested. Successive campaigns of Chinese propaganda aimed at questioning the U.S. commitment to Taiwan have also helped to fuel a domestic narrative that the United States will abandon Taiwan. The phenomenon is so ubiquitous in Taiwanese discussions that it even has its own term in Mandarin: yimeilun (疑美論), or “U.S. Skepticism Theory.”

Confidence in Japan has not wavered in the same way. As Chen put it in a 2022 interview with Voice of America, “There are plenty of U.S skeptics, who all day espouse ‘U.S. skepticism theory,’ but in Taiwan, you won’t ordinarily find a ‘Japan skeptic.’” Chen plans to conduct a poll in the next several weeks to see how Takaichi’s remarks have impacted this view.

As for the Japan-China bilateral relationship, the temperature is likely to remain frosty for the near future. Both countries may be feeling especially “emboldened” right now, as Syracuse University political scientist Margarita Estévez-Abe put it to the Financial Times, in the wake of successful recent meetings with U.S. President Donald Trump. And China, which just celebrated the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with a massive military parade, is not prone to look especially kindly on Takaichi. Chinese state media has long focused on Takaichi’s multiple visits to Yasukuni Shrine, including one this past summer, and her history of revisionist comments about Japan’s wartime behavior. After her election as prime minister, Chinese leader Xi Jinping pointedly did not extend Takaichi the same public congratulations he gave to her three most recent predecessors.

In the coming days, attention will center on the bilateral fallout between China and Japan. But the audience that matters most isn’t in Tokyo or Beijing—it’s in Taipei.

Dan Spinelli is a first-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Southern California, where he studies institutions and governance issues in East Asia. He previously was a program specialist for the China team at the U.S. Institute of Peace, where he focused on cross-Strait issues. Dan has a master’s degree in Asian Studies from Georgetown University and a bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Pennsylvania. Before going to graduate school, he worked as a national security reporter for Mother Jones magazine in Washington, DC. He is a proud native of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.