“Without a doubt.”

When I asked my father whether Toyota had changed our hometown, he was unequivocal. A day-one employee at what became Toyota’s largest global manufacturing hub, he spent more than 12 years on its assembly lines in Georgetown, Kentucky. But before Toyota arrived, he worked at Johnson Controls, an automotive seating plant that supplied the town’s struggling domestic auto industry. “Everything else had folded up. I was sure I was going to lose my job,” he said. “There just wasn’t much of a future for us without Martha Layne.” Without her determination to bring Toyota to Kentucky, Georgetown’s automotive industry and my family’s livelihood would have disappeared entirely.

In today’s fractured geopolitical landscape, Collins’ model for personal, subnational diplomacy offers a blueprint

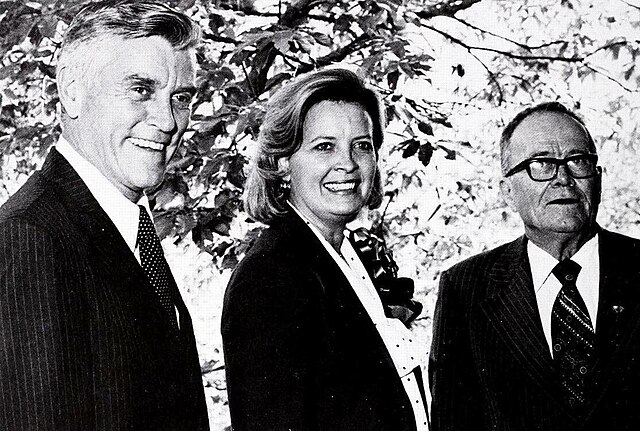

Former Kentucky Governor Martha Layne Collins passed away last month at age 88. To most of Georgetown, she was simply “Martha Layne,” the woman who staked her sole term as governor on bringing Toyota to our community in 1985. Collins convinced the global automaker to bet on my hometown, defying critics at home and the anti-Japanese sentiment then roiling American manufacturing. Over the next four decades, she dedicated herself to nurturing the U.S.–Japan partnership, believing that diplomacy driven from the ground up could reach beyond the limits of national politics. In today’s fractured geopolitical landscape, Collins’ model for personal, subnational diplomacy offers a blueprint for safeguarding crucial international ties when government-to-government relationships falter.

The former schoolteacher seemed an unlikely candidate to save Kentucky’s declining automotive sector. Georgetown needed an economic lifeline, and workers like my father were running out of options. Kentucky’s governors were limited to a single, non-consecutive term, giving Collins just four years to act. With limited political capital, Collins’ pursuit of Toyota was both politically risky and strategically bold. Still, she had already proven herself nationally, chairing the 1984 Democratic National Convention, where she was vetted as a potential running mate for Walter Mondale. That profile helped her make a case few governors could, or would risk: that Kentucky was not just offering one-time tax breaks, but a lasting partnership.

Collins worked to earn Toyota’s trust through repeated visits to Japan, learning basic Japanese phrases, and familiarizing herself with Japanese business practices. By prioritizing relationship-building and mutual respect over the aggressive salesmanship of other state governors, her persistence paid off. In December 1985, Toyota president Dr. Toyoda Shoichiro announced the Georgetown plant with language that transcended mere business interests. “This manufacturing plant marks a significant advancement in our dream of achieving a full partnership with the American people,” he said. “During our entire history in the United States, we have been touched and rewarded by Americans reaching out to us. Today, we begin the newest phase of our relationship by reaching out to you.”

That language mattered, at a time when anxiety about Japan’s economic ascendance had soured American public opinion and made proactive engagement politically risky. Collins’ detractors at home were unsparing. She later recalled bumper stickers reading “Collins: Best governor Japan ever had.” They invoked World War II memories, with older Kentuckians who remembered the Pacific conflict casting Japanese investment as a threat to American sovereignty. But Collins’ persistence, matched by Dr. Toyoda’s language of reciprocity—Americans reaching out, Japan reaching back—gradually disarmed that resistance.

What set Collins apart was not just closing an $800 million deal that initially promised some 3,000 jobs, but her commitment to nurturing the U.S.–Japan relationship for four decades after leaving office. In 1991, she became Honorary Consul-General of Japan in Lexington, serving for over 30 years until her death. Through her leadership of the Kentucky World Trade Center and the Japan/America Society of Kentucky, Collins advanced exchange grounded in a simple conviction: enduring partnerships rest on personal commitment and people-to-people ties that outlast any term in office. Japan honored her with the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star—one of the country’s highest civilian honors—recognizing her lifetime of service. The landscape Collins navigated forty years ago—heightened trade tensions and nationalist-inflected protectionism—remains strikingly relevant today. Recent U.S. policies, such as high tariffs and increased pressure on Asian allies, have revived uncertainty about Washington’s commitments. But when leader-to-leader relationships shift with political cycles, stable subnational partnerships become even more critical.

Collins demonstrated why the U.S.–Japan relationship has endured through periods of national political strain: subnational partnerships like the Kentucky–Toyota relationship continued to deepen regardless of shifts in Washington. That partnership weathered multiple presidential administrations, trade disputes, and policy shifts because of mutual benefit and close people-to-people ties that national diplomacy, constrained by political cycles, struggles to replicate. Personal commitment was decisive. Collins treated Toyota not as a transaction, but as a lifelong relationship, investing in resilience and mutual benefit over headlines. Her four decades of bridge-building show how subnational diplomacy can stabilize international ties when national politics waver, precisely because regional leaders have deeper local stakes and longer time horizons than their federal counterparts.

When I asked my father about Martha Layne, he didn’t talk about politics or diplomacy. He talked about the home our family could afford, college tuition paid, and the security of a stable retirement. That is the reality of subnational diplomacy and the U.S.–Japan partnership: Collins’ enduring example of how leaders outside Washington, through sincere commitment to mutual benefit, forge ties that outlast the unpredictable swings of national political cycles. Toyota’s $2 billion in new investments in Kentucky this year alone means another generation will have the same opportunities we had—perhaps more. Though Collins did not live to see the company’s newest facilities open in 2027, her example of patient, personal diplomacy endures.

A native of Georgetown, Kentucky, Duncan is a J.D. candidate at American University's Washington College of Law.