Tokyo Review invited me to take a critical look at an essay I published in Foreign Policy thirty years ago, when I was a junior diplomat at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. In that piece, ambitiously titled “Revolutionizing America’s Japan Policy,” I argued that U.S. policy toward Japan in the mid-1990s needed a fundamental overhaul to better align with the post–Cold War global environment and the evolving dynamics of East Asia. I also contended that such a recalibration had to grapple directly with the contentious U.S.-Japan trade friction that dominated bilateral relations during the first term of Bill Clinton’s presidency.

At the time—about a half-decade after the demise of the Soviet Union but before China’s full emergence on the world stage—the United States was the sole global superpower. Regardless of U.S. preeminence, America’s bilateral alliance with Japan remained central to Washington’s strategy in Asia. In those years, the relationship was characterized by a strong (if lopsided) alliance on the security side, but intense trade-policy friction on the economic side. Meanwhile, Japan was showing signs of drifting away from Washington while taking a relatively benign view of China’s rise.

In that context, I critiqued the prevailing U.S. approach to Japan as overly reactive and too narrowly focused on maintaining the alliance’s status quo. The United States was intent on keeping Japan content in its role as a junior security partner while simultaneously assailing it aggressively as an economic threat. Washington was failing to recognize Japan’s potential as a multidimensional actor in Asia and a comprehensive regional partner.

To address these shortcomings, I proposed several ambitious reforms aimed at “revolutionizing” the bilateral relationship. Most importantly, I argued for deepening—rather than blocking—bilateral economic integration through the creation of a comprehensive Japan–America Free Economic Agreement (JAFEA). Such an agreement, I maintained, would not only reduce persistent trade frictions but also create a broader and more stable economic foundation to underpin the U.S.-Japan strategic partnership. The bulk of my essay laid out a detailed roadmap for negotiations focused on reducing trade barriers, accelerating Japanese economic deregulation, dismantling the nation’s exclusive, bank-centered keiretsu business networks, advancing financial market integration and macroeconomic rebalancing, and generally increasing bilateral economic interdependence through greater cross-investment and more ambitious joint efforts in technology and energy security.

Amid the sharp debates of the late 1980s and early 1990s between the “alliance managers” at the State Department and the “trade warriors” at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, I found fault with both camps. I argued that the “alliance managers” were wrong to downplay the reality that “Japan is different” economically. At the same time, I contended that the “trade warriors” defined differences in trade practices too narrowly, on a sector-by-sector basis, in a manner that would ultimately fail due to insufficient leverage to resolve deep-seated structural issues.

In place of these approaches, I advocated a “grand carrot” strategy to generate positive leverage in favor of economic integration. I argued that deeper U.S.-Japan economic integration would ultimately embed Japan more fully in like-minded global economic governance structures while reinforcing U.S. leadership in Asia.

So what happened after I published that essay and its bold proposals? Clearly, my grand plan was not implemented, which is hardly surprising. But was the underlying vision of strengthening the U.S.-Japan alliance through extraordinary efforts toward economic integration valid in the first place?

I believe four major developments shape the retrospective analysis.

First, Japanese economic growth stalled, and the perceived Japanese economic “threat” that had fueled a cottage industry of Western books with titles such as Japanophobia and The Coming War with Japan faded along with the dramatic collapse of Japan’s growth trajectory. Only a couple of years after Foreign Policy published my treatise on how to contend with disruptive Japanese economic power, I found myself working long hours at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo tracking the collapse of Japanese banks and securities houses against the backdrop of the broader Asian Financial Crisis.

Second, China grew faster and became more powerful—and more threatening to both Japan and the United States—than anticipated. This shift profoundly affected Japanese attitudes toward the United States, including on trade and investment policy. Japan abandoned the idea of a “Look East” strategy and lost confidence in its ability to serve as the economic fulcrum between the West and Asia.

Third, the United States did, remarkably enough, attempt a facsimile of my JAFEA strategy toward Japan—albeit on a plurilateral rather than bilateral basis. By 2004, I was deeply involved in launching free trade agreement talks with South Korea, followed soon thereafter by broader negotiations under the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Throughout these efforts, my colleagues and I in the George W. Bush White House viewed the ultimate prize as Japan’s inclusion in a binding and comprehensive trade and investment liberalization agreement. By 2007, the United States signed the United States-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS); by 2011, that agreement was ratified, and Japan was persuaded to join the thirteen-nation TPP, whose negotiations were successfully completed in 2015.

Fourth—and most dramatically—the United States subsequently retreated from its own strategy and abandoned the TPP following intense criticism of trade liberalization during the 2016 Hillary Clinton–Donald Trump election showdown. The political reasons for America’s reversal are complex and are the subject of extensive discussion in my Georgetown University course on Indo-Pacific economic diplomacy. Rising income inequality, technological change, manufacturing job losses, and the electoral importance of the Great Lakes region have all played a role.

Perhaps most remarkable is that today it is Japan—not the United States—that is carrying the banner of a rules-based international economic order across Asia. Japan is now the country most consistently advocating the kind of free, open, transparent, and fair trade and investment liberalization that I called for in the mid-1990s as a key means of strengthening the U.S.-Japan alliance.

Meanwhile, the U.S.-Japan alliance relationship appears remarkably resilient, even if it now rests largely on a single pillar of shared national security interests amid an increasingly dire regional geopolitical environment.

U.S.-Japan ties would undoubtedly be stronger—and more stable—if they were anchored more firmly in a robust tripod of shared geopolitical objectives, shared economic integration goals, and shared human values.

It is inherently challenging to make predictions about grand trends. But I am personally pessimistic that the United States will shake free from its current protectionist approach to international trade and investment within the next decade. I am more hopeful that America will escape its current anti-democratic funk and re-embrace liberal political values in a way that will restore respect for America in Japan, thus buoying U.S.-Japan trust and cooperation.

Certainly, much has changed in the past 30 years, and I expect that new changes will continue to surprise us in the decades ahead.

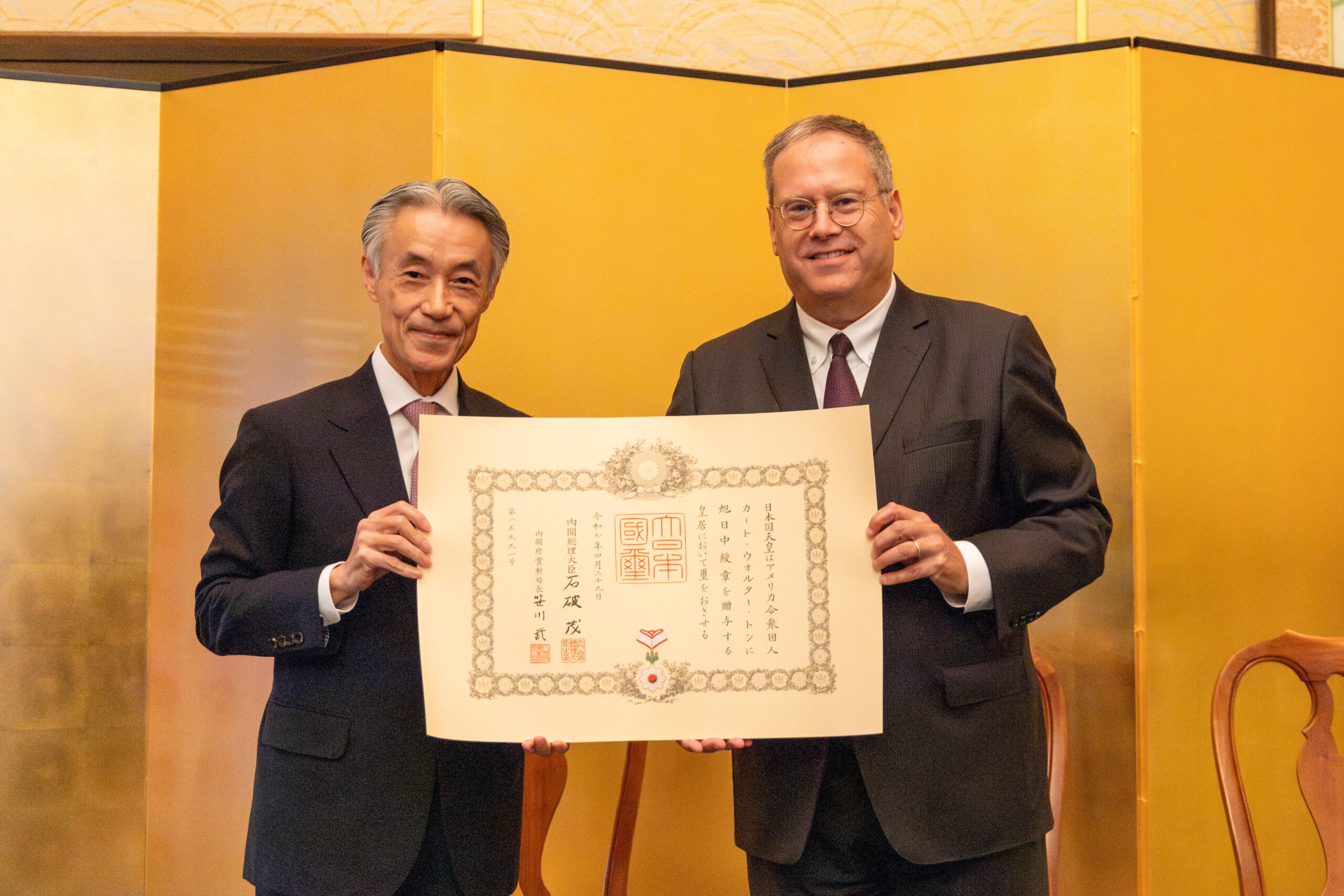

Ambassador Kurt Tong is a Managing Partner at The Asia Group. He was a U.S. diplomat from 1990 to 2019, including tours in Tokyo in 1995-99 and 2011-14. He teaches at Georgetown University and International Christian University (ICU), and studied Japan affairs at Princeton University, the Inter-University Center in Japan, Tokyo University, and ICU.