The Shangri La Dialogue came and went, and while many nations took a measured tone towards North Korea at the conference, Minister of Defense Itsunori Onodera carried a different message from the Japanese government:

“As defense authorities, we have two major roles to play in resolving these issues. The first role is to maintain current maximum pressure on North Korea in tandem with diplomatic efforts…The second point is to maintain and strengthen deterrence.”

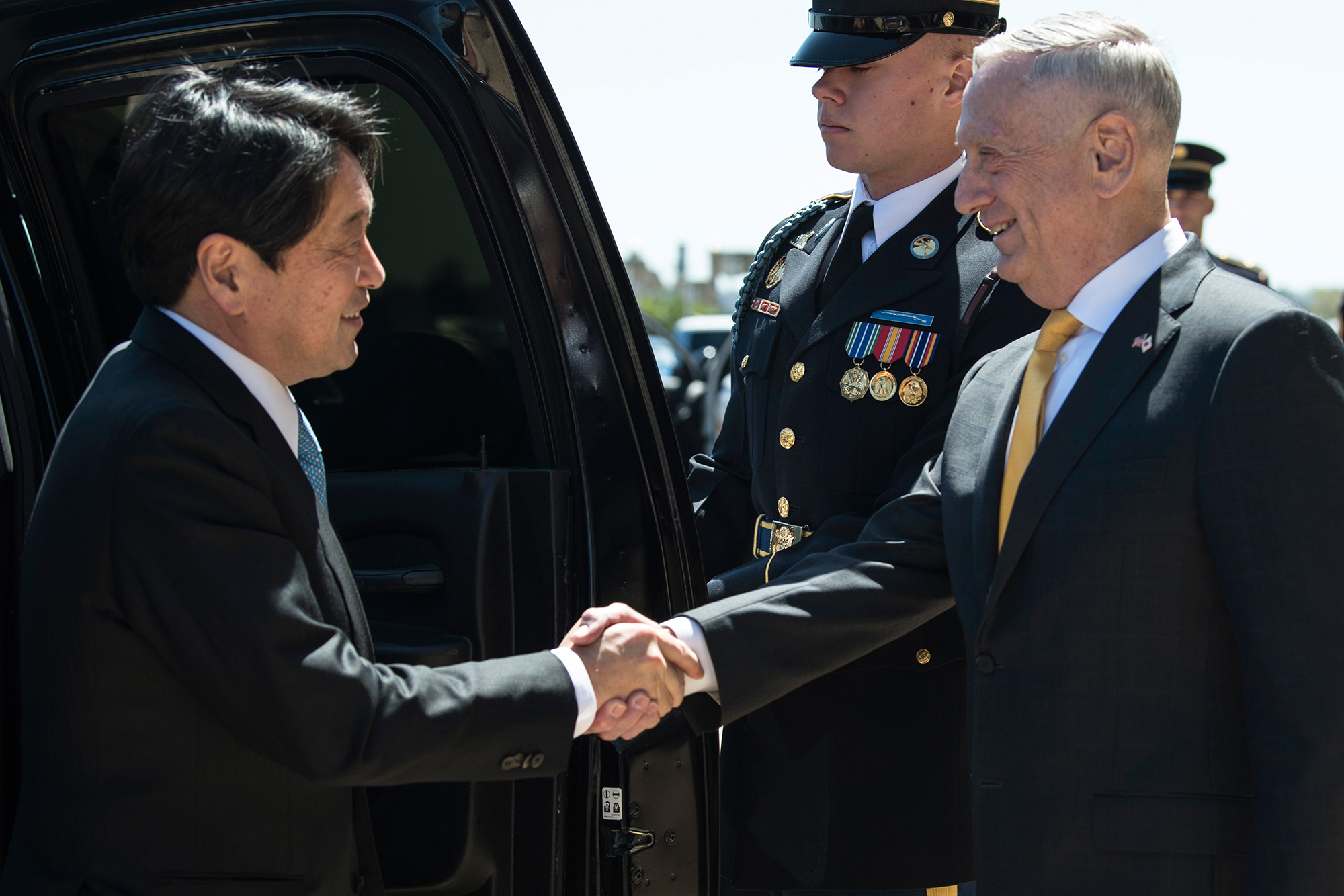

This message was echoed in Prime Minister Abe’s meeting with President Trump in Washington DC this week. The Abe administration’s adherence to the maximum pressure campaign may lead some to question Japan’s policy position, especially as the Moon administration in South Korea takes a much softer stance towards the Kim regime following the Panmunjom Declaration.

Certainly, Japan has its reasons for taking this posture, but it does beg a few questions for outside observers:

What is the “Maximum Pressure” Campaign?

The “Maximum Pressure” (saidaigen no atsuryoku) campaign is a concerted multinational effort aimed at isolating North Korea and draining resources that could be used for provocative behavior; for example, sanctioning fuel trade to degrade the DPRK military’s ability to fuel and launch their missiles.

The pressure campaign employs all instruments of national power. Diplomatic efforts to date have sought to leverage other countries to sever North Korea’s ties abroad, including the expulsion of North Korean diplomats and imposition of travel restrictions. The information arm of the campaign focuses on intelligence sharing among strategic partners and public broadcasting of North Korea’s activities. Most recently, this has come in the form of publishing information on sanctions violations. Military operations have focused on forward posturing of military assets and strategic shows of force, such as the SDF’s participation in exercises with three U.S. carriers in the Sea of Japan last November. Finally, economic power has been applied through primary and secondary sanctions.

There are three overarching objectives of the pressure campaign. The first is to drain North Korean resources, both directly impacting nuclear and missile development and forcing the Kim regime to make decisions about opportunity cost for investment elsewhere. The second is to push North Korea towards the negotiating table (i.e. the “off-ramp”). The third is to arrange the position of military forces in the region in case the first two objectives fail and a crisis escalates.

When did the Pressure Campaign begin?

The genesis of Japan’s maximum pressure campaign was well before the Trump administration adopted its current strategy to bring about change in North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. The first inkling of a Japanese desire to increase pressure against the Kim regime emerged following North Korea’s September 2016 nuclear test. After an emergency meeting of Defense Trilateral Talks representatives as well as a meeting of the Alliance Coordination Mechanism’s Director General-level members, the Abe administration decided to execute its first ever bomber escort mission in conjunction with the United States and South Korea as a show-of-force and a step towards trilateral, operational response to North Korean actions.

When missile provocations continued in 2016, the Japanese government incrementally advanced and routinized its military posturing in response to North Korean provocations. Certainly, the Japanese government would have wanted to do more, but there were limitations to how much could be done if Japan were to go it alone.

The opportunity to advance this approach came when the Trump administration took over in 2017 and decided to execute its own pressure campaign against North Korea. Now, Japan had backing from its ally to turn up the heat through employment of the full spectrum of instruments of national power.

Why is Japan so adamantly committed to the pressure campaign?

The United States has backed off the rhetoric associated with the pressure campaign ahead of the June 12th summit. It appears that the South Korean government intends to forgo it all together in favor of diplomatic engagement. Meanwhile, the Japanese government remains firmly committed to continuation of the pressure campaign, believing that it sets the stage for realistic progress on removal of North Korean nuclear and missile capabilities, with the added interest of resolving the abduction issue. There are five reasons why the Abe administration remains firmly rooted in this approach:

- Reprisal

Although it is frequently discussed in the LDP’s emergency meetings following North Korean provocations, an oft-overlooked reason for Japanese involvement in the Maximum Pressure campaign is that it encompasses Japan’s retaliatory action for North Korean provocations. When North Korea launches a missile over Japanese territory or one lands in Japan’s EEZ, there is inherent threat to Japanese personnel and property. Of course, Japan seeks to deter future provocations, but there is a desire for inflicting punishment underwriting Japan’s pressure campaign against North Korea.

- Trust deficit

Within the Japanese government, there is deep institutional memory of failed diplomacy with North Korea, especially among members of the Abe administration. Prime Minister Abe and his closest political cohort were part of the team behind the Koizumi-Kim Jong Il summit in 2002. The Japanese government then enjoyed similar results to those the United States has received so far – return of detainees and allusions to cessation of provocative behavior in exchange for economic and other concessions. In Japan’s case, the agreed-upon missile moratorium lasted from 2002 until 2007, at which point the North not only resumed its missile launches but revealed ever-increasing capability.

Japan was also a member of the Six-Party talks from 2003 to 2007 that led to promises of denuclearization. Of course, those negotiations were unsuccessful in meeting those objectives. Most recently, the Abe administration shepherded six rounds of diplomatic talks with North Korea between 2012 to 2014. The primary thrust of those talks were the abduction issue, and North Korea abruptly ended those discussions before ramping up the provocations that eventually led to the start of the maximum pressure campaign a few years later.

In sum, the Japanese government, and the Abe administration in particular, has a strongly held trust deficit when it comes to North Korea. The administration firmly believes that the Kim regime will not change its course without sufficient application of pressure across the full spectrum of power.

- Protection of Japanese interests

Without a seat at the diplomatic table with North Korea, the Japanese government faces the prospect of having its interests left outside of ongoing negotiations altogether. Although the Japanese government would like the abduction issue to be addressed, its primary area of concern is short and medium range ballistic missiles – which are of less import to the United States and South Korea. Furtherance of the pressure campaign offers two potential outcomes in support of Japanese interests: the U.S. and South Korean governments carry the water for Japan in order to gain Japan’s acquiescence in relaxation of the pressure; and Japan maintains a bargaining chip that could result in its own bilateral talks with North Korea.

- Impetus for strengthening Japan’s strategic partnerships

The pressure campaign has also seen success in drawing international support, especially in the area of Japan’s strategic partnerships. Japan opened the door for greater military cooperation with nations “with whom it has a close relationship” (kinmitsu na kankei) in its 2015 Peace and Security legislation, and the pressure campaign has paid dividends in advancing the implementation of closer ties. The United Kingdom and France are increasing their respective maritime presences in the region, partly in response to the North Korean threat. Further, Canada and Australia are set to deploy reconnaissance aircraft to Kadena air base in Okinawa to support United Nations sanctions enforcement. Thus, continuation of the pressure campaign not only serves to tighten the grip on North Korea but has the added benefit of enhancing Japan’s security ties with its strategic partners.

- The Abe administration sees results

More than most countries, Japan has reason to believe the pressure campaign is impacting North Korea. With record number of “ghost ships” washing ashore on Japan’s coastline, it suggests that North Korean fishermen are being forced to go further out and stay out longer at sea to compensate for shortages due to sanctions. Also, Japan’s sanction monitoring activity has shown that North Korea is having to pursue workarounds to acquire resources from international parties. While the true impact of sanctions remains contested, these patterns of change suggest to the Japanese government that continuing to squeeze the Kim regime under the pressure campaign could impact North Korea further and yield greater leverage at the negotiating table.

So what’s next for Japan and the pressure campaign?

For Japan, the path ahead is about staying the course with its current approach while doing what it can to influence the Trump and Moon administrations’ respective dealings with North Korea. Onodera met with his U.S. and Korean counterparts at Shangri La. Abe visited the United States this week to advocate for Japan’s interests and reaffirm U.S. commitment to the pressure campaign. After that, the Japanese government will be watching the US-North Korean summit closely and seeking an immediate readout of the events.

Meanwhile, Japan will do what it can to keep the pressure on North Korea. The Self Defense Force and Coast Guard will continue sanctions monitoring, broadcasting any violations they detect. The Japanese government will also bolster its relationship with any party willing to ratchet up pressure against North Korea; namely, the UN Command “sending states” like Australia, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom.

Will any of this work to create different outcomes from past encounters with North Korea? The bottom line is that the Japanese government believes that with an unprecedented amount of pressure applied, it might.

Explore more of our North Korea articles:

[posts-by-tag tags=”North Korea” number = “5”]

Michael MacArthur Bosack is the special advisor for government relations at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies. He previously served in the Japanese government as a Mansfield Fellow.