Sunday, December 15 marked 53 years since the murder of a Japanese postwar icon Rikidōzan. Some may know of him as the Godfather of Japanese puroresu (pro wrestling), but that’s only part of the story. His life rests at the intersection of Northeast Asian culture, history, and identity, offering the outside observer a window into the complexities that lie in the relationship between regional neighbors.

For most Japanese, Rikidōzan’s story begins in 1953. The postwar occupation had just ended the year prior. The Korean War was in its last throes, with Japan providing support to allied operations as a rear area base. The economy was rebuilding, as was the country itself.

Nearly a decade after World War II ended, things were starting to return to normalcy. Sports and entertainment, in particular, were back in full swing, and new trends started to take root with the influx of western culture that came from seven years under Allied occupation. After all, there were a few hundred thousand soldiers from the United States and British Commonwealth spread throughout Japan. Armed Forces Radio had been broadcasting from Yokohama since September 1952, less than a month after U.S. forces arrived in the country. The Stars and Stripes newspaper had set up shop in central Tokyo, and foreign correspondents that had been expelled or interred were free to report in Japan as they had been up until the late 1930s. U.S. government-sponsored morale tours brought athletes and performers to Japan, and new fads started to sweep across the country.

The “sport” of pro wrestling exploded across postwar Japan

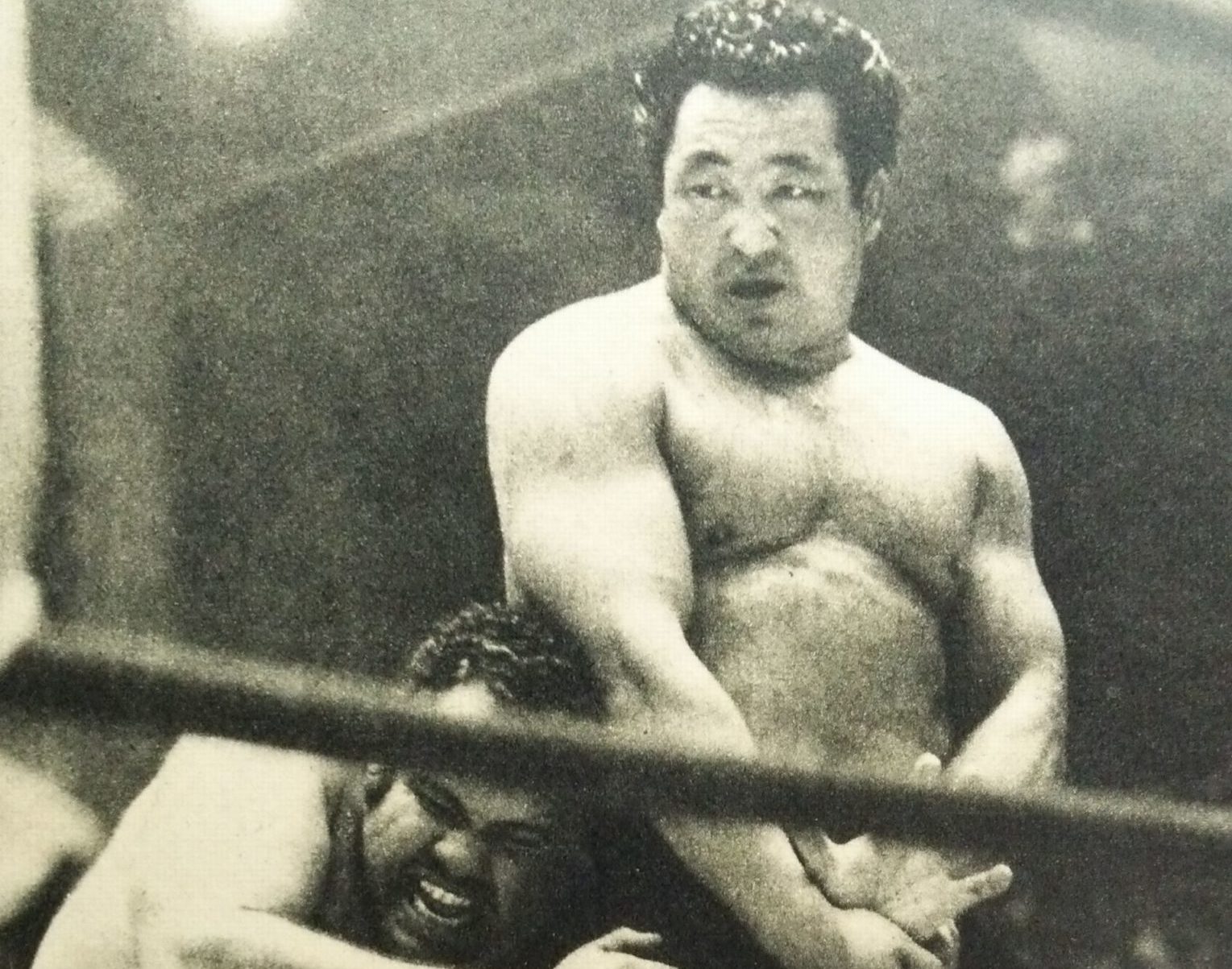

Among the trends to catch on was professional wrestling, which may seem gimmicky to many, but it captured the imaginations of many Japanese in the immediate aftermath of the Allied occupation. Broadcast on television and radio with live bouts in various arenas throughout the country, the popularity of the “sport” exploded in the immediate postwar era – so much so that thousands of people used to huddle together en masse in public squares like Shimbashi to watch the matches broadcast on a handful of tiny television sets.

Most Japanese did not watch wrestling to see the American heroes of the time like the Destroyer, Lou Thesz, Freddie Blassie, or any of the other big name foreigners that toured Japan at the time – they watched for Rikidōzan. Following Japan’s defeat in WWII and its occupation by allied forces, here was a former Sumo wrestler who fought for Japan, going toe-to-toe with and defeating the hulking foreigners on television sets and becoming a symbol of postwar Japanese strength.

The irony here is that Rikidōzan was not Japanese – he was born Kim Sin Rak in what is now South Hamyong Province, North Korea. When his father died at an early age, the young Kim traveled with a talent scout to Nagasaki and took the name Momota Mutsuhiro in search of opportunity.

The practice of Koreans moving to Japan during the period of Japanese colonization was not unusual, nor was the adoption of Japanese names. Some young Korean men were impressed into Japanese military service, others headed to Japan in search of work, and, during the war, the Japanese government brought an estimated 700,000 to 800,000 Koreans to Japan to serve as laborers.

Here was a former sumo wrestler, fighting and beating foreign foes and becoming a symbol of postwar Japanese strength

Some Koreans, like Rikidōzan, adopted Japanese names to avoid discrimination while searching for employment during the colonial period. For others, Japanese names were forced upon them, especially following the imposition of the sōshi-kaimei ordinances which pressured Koreans to adopt Japanese names. Some notable Koreans who once held Japanese names included former South Korean President Kim Dae-jung, who was once Toyota Daiju, and long-time Korean dictator Park Chung-hee, who went by Takagi Masao.

Even with a Japanese name, the economic prospects for a family-less teenage zainichi Korean was grim, so the newly-named Momota took a path that many rural, disadvantaged Japanese embarked on at the time to try to gain fame and fortune – he joined a sumo stable to become a rikishi, or sumo wrestler. As with other sumo wrestlers, he received a rikishi name: his was Rikidōzan (力道山). He was successful in the Sumo ring, too. Rikidōzan competed in 23 Grand Sumo tournaments and rose to the third highest rank of Sekiwake. Even though nowadays Mongolian-born wrestlers dominate the sport, in the pre-war era, the Sumo world of Rikidōzan’s time was not yet open to foreigners and he knew there would be a glass ceiling because of his family heritage.

Of all sports, Sumo is the one that Japan has tried the hardest to isolate as its own. The ritual, the ties to Shintoism, and the millenia-old historical relevance of the sport led to a deep-seated apprehension towards inclusion of non-Japanese. While non-ethnic Japanese like Rikidōzan found their way into Sumo stables, the discretionary system of promoting wrestlers to the highest ranks of Ozeki and Yokozuna meant that no one with non-Japanese family roots could have any hope to achieve those ranks. In fact, the first foreigner to reach the highest rank of Yokozuna was Chad Rowan, aka Akebono, who managed the feat in 1993.

Through pro wrestling, Rikidōzan became a Japanese icon

Given his lack of prospects in Sumo, Rikidōzan found an opportunity to transition to the world of pro wrestling during the Occupation era. He trained and performed in different locations in the United States, though most famously in Honolulu. Then, in 1953, Rikidōzan returned to Japan to start his own pro wrestling venture: the Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance.

Through puroresu, Rikidōzan became an icon in postwar Japan. What the public knew at the time was that Rikidōzan started his own wrestling company, recruited young talent (like the future megastar/politician Antonio Inoki), and invested in clubs, hotels, and other businesses. What the public did not know was that when Rikidōzan took trips to western Japan for “vacation,” he would disappear for a few days at a time, sailing across the Sea of Japan to visit relatives in North Korea (something that Inoki detailed in his 2014 book, Fighting Spirit Diplomacy). Although Rikidōzan never bought into the DPRK ideology, he continued to maintain ties to the hermit kingdom.

By no means was Rikidōzan alone in this practice. In fact, North Korea’s ties to segments of the Japanese population have long been known. The most notable example is the Chõsen Sõren, a group dedicated to preserving links to North Korea. Less known are the Korean schools (Chõsen gakko) in Japan which do their best to emulate North Korean culture with Korean language instruction, use of traditional dress, courses on Korean identity, and even portraits of members of the Kim regime hanging in the classrooms. Like Rikidōzan, few Zainichi Korean families who choose to send their children to those schools actually buy into the DPRK ideology, but it is the only affordable option for their children to receive an education in Korean and a maintain a connection to their ethnic heritage. Even so, these same children often use their Japanese names outside of the school, and, like Rikidōzan, maintain a dual identity. Interestingly, many of these zainichi families are without nationality. Following World War II, ethnic Koreans in Japan were given the choice to accept South Korea citizenship or to become “Chosen-seki,” meaning “Korean” citizen. The latter option meant that these residents of Japan, while covered under the 1947 constitutional provisions for kokumin (residents of Japan) were, by diplomatic definition, stateless.

Rikidōzan’s penchant for secrecy would ultimately help contribute to his untimely death

Rikidōzan’s penchant for secrecy eventually contributed to his untimely death. His non-wrestling “pursuits” and love of the nightlife saw him crossing paths with the Yakuza. In December 1963, he got into an altercation with a young gangster, who stabbed him in the torso. Rikidōzan, wanting to avoid the media maelstrom that would have followed his visit to a traditional emergency room, settled on an outpatient stitch up. The stories from there vary greatly, but he eventually died from complications from the wound and the secrecy behind the exact circumstances of his death has caused speculation to abound.

After his death, his protege Antonio Inoki took up the mantle and carried forward Rikidōzan’s legacy. For Inoki, this meant not only elevating wrestling’s status in Japanese pop culture, but also maintaining the connections to North Korea. Eventually, Inoki became a member of Japan’s House of Councillors with the aim of using sports to achieve diplomatic breakthroughs – a prime target was North Korea, and he traveled to the country over 30 times, including a big event in the mid-nineties.

In 1995, Inoki coordinated and performed in a pro wrestling event in Pyongyang known as the “Collision in Korea.” While the whole spectacle is worthy of an entire feature of its own, one unforeseen consequence of this event was burgeoning DPRK interest in Rikidōzan.

Starting in 1995, North Korea tried to adopt Rikidōzan, or ‘Ryeokdosan’, as its own. The government put his face on stamps and commissioned prose and comic biographies (both were translated and sold abroad). The core theme of those propaganda efforts were always the same: Korean man becomes champion in Japan by defeating Japanese and Americans.

The memory of Rikidōzan has since faded in both Japan and the Korean Peninsula, but with historical issues once again plaguing diplomatic relations in the region, it is worth remembering this icon. Certainly, there are other symbols of how interwoven the culture, identity, and history of Japan and the Korean peninsula are, but few as vibrant and dynamic as Rikidōzan, the zainichi Korean symbol of postwar Japanese strength.

Michael MacArthur Bosack is the special advisor for government relations at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies. He previously served in the Japanese government as a Mansfield Fellow.